What I Learned Building an App at 72 — and Why It Changed How I Think About Our Stuff

A personal essay about building Stuffolio, learning something new later in life, and finding a calmer way to manage the things we own.

This wasn’t part of some grand plan. I just wanted something new to work on, something to keep my mind engaged. What I didn’t expect was that it would turn into an actual app.

There were plenty of false starts. More than a few “Damn, I think I need to start over” moments. And an embarrassing number of times I told myself, “I’ll just add one more feature.”

It took much longer than I expected, but I learned a lot along the way. And somehow, it turned into something I’m genuinely excited to share.

It started with a manual

The idea for the app, which I eventually named Stuffolio, didn’t come from a brilliant insight. It came from standing in front of something that wasn’t working and thinking, I know I’ve seen the manual for this … somewhere.

That moment kept repeating itself.

I was always looking for the same things: manuals, serial numbers, setup instructions, repair videos, or trying to remember whether a warranty was still valid or had quietly expired. Sometimes the information was in a folder. Sometimes it was buried in an email. And more often than I’d like to admit, it was in “that drawer.”

You know the one.

Eventually, I had to admit that "that drawer" was not a filing system.

So I built something simple: a place to keep track of what we own, along with the information we actually need — warranty dates, manuals, support contacts, even online help videos. One place instead of twelve.

But as I worked on it, the questions got bigger.

My wife and I started looking around our home and asking ourselves: Where did all of this stuff come from? And maybe more importantly, what are we eventually going to do with it?

Things have a way of accumulating quietly. Some we bought. Some were gifts. Others just seemed to appear over the years. Along the way, we assumed certain items would naturally become heirlooms — things we’d pass down to our daughters because they mattered to us.

What we’ve learned, sometimes gently and sometimes not, is that what feels meaningful to one generation doesn’t always feel that way to the next. Some of the things we thought our kids would treasure turned out to be things they simply don’t want.

That led to a different kind of question. How do you even talk with your kids about that? Not as a legal conversation, and not as something heavy or uncomfortable, but as a practical way to make things easier for them later?

So we tried it.

One evening, we FaceTimed our two daughters and walked through some of the things we’d always assumed they’d want. The oak school desk we’d picked up at a yard sale. A set of china that had been in the family for decades. Pieces we’d collected while traveling.

They were honest with us. The desk wouldn’t fit either of their lives. The china wasn’t their style. But a few things surprised them — items we’d almost overlooked meant more to them than we expected. And some things we thought were just ours, one daughter asked if she could have someday, while the other had no interest at all.

It was clarifying for everyone.

It wasn’t a difficult conversation. It was a relief. One we’ll have again.

That’s when I caught myself thinking, Ah — another feature.

I added something I eventually called Legacy Wishes: a simple way to leave context behind. We could describe an item, note why it mattered, and indicate which of our daughters might want it. Just as important, it gave them a way to tell us if they didn’t. If neither wanted something, we could note whether to donate it, sell it, or let it go.

It wasn’t about control or planning everything out. It was about clarity — and removing a little uncertainty for everyone involved.

Learning something new later in life

Building the app became its own education.

I started the way a lot of people do now: watching instructional videos and trying things out, often without fully understanding what I was looking at. I spent a lot of time staring at development screens thinking, Well, that didn’t work.

Along the way, I discovered that modern AI tools could be surprisingly helpful. At first, it felt like they were doing too much of the work, and that made me uneasy. But over time, something shifted. They stopped feeling like a replacement and started feeling more like an airplane — and I was the pilot.

They could help with navigation and smooth things out, but I was still deciding where to go and when to land.

As I got more comfortable, I noticed something else. I wasn’t just asking questions anymore. I was pushing back, debating answers, and occasionally correcting the tools themselves. Sometimes I was clearly the student. Other times, I found myself in the role of teacher.

That back-and-forth is where the learning really stuck.

What mattered most was that the learning was still mine. The tools didn’t replace effort or judgment. They supported it. Slowly, things that once felt completely opaque started to make sense.

It reminded me that learning later in life isn’t about speed. It’s about curiosity, patience, and being willing to feel uncomfortable long enough for things to click.

A clearer way to think about the future

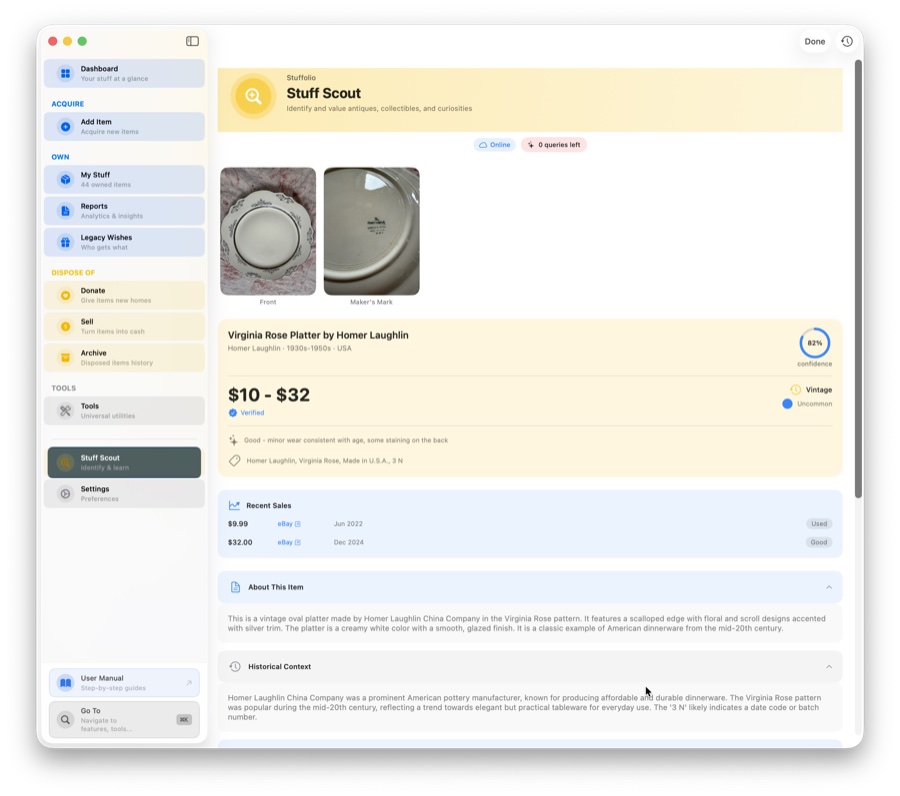

One afternoon, we were in a Goodwill store and came across a set of dishes that looked familiar. I took a quick photo, ran it through Stuffolio, and learned just enough about what they were and what they were worth to make a simple decision.

We passed. We already have too much stuff.

That was the whole point. I wasn’t looking for a perfect answer. I just wanted enough information to decide and move on — the same kind of clarity I wanted to leave for our daughters.

Somewhere along the way, the technical questions gave way to more personal ones. Would someone know what this is? Would they understand why it mattered, or feel comfortable letting it go? Would the people I care about most be left guessing — or have enough context to decide for themselves?

I realized we don’t need more complexity. We need clarity, on our own terms.

That’s what I tried to build. And honestly, that’s what I’m still figuring out — like everyone else at this stage of life, trying to make a little more sense of the things we own and what they mean … if anything at all.

Terry Nyberg, 73, is a lifelong learner who built Stuffolio after finally admitting that the top drawer was not, in fact, a filing system.

—

If the lifecycle approach resonates, see how Stuffolio implements it on the Features page — and how Legacy Wishes and Family Sharing fit together on the Family Sharing page.